Under-Represented Groups in Education (U.R.G.E.) hosted their monthly Governance Forum last Friday, Feb. 28 titled “Before the First Three: Reckoning with Tech’s History and Realizing a Better Future.” They partnered with the Georgia Tech Library, National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (GT NAACP) and the Organization for Social Activism (OSA). Presenters from each organization led the talk and held a town-hall-style forum at the end for audience members to ask questions, raise concerns and have an open discussion.

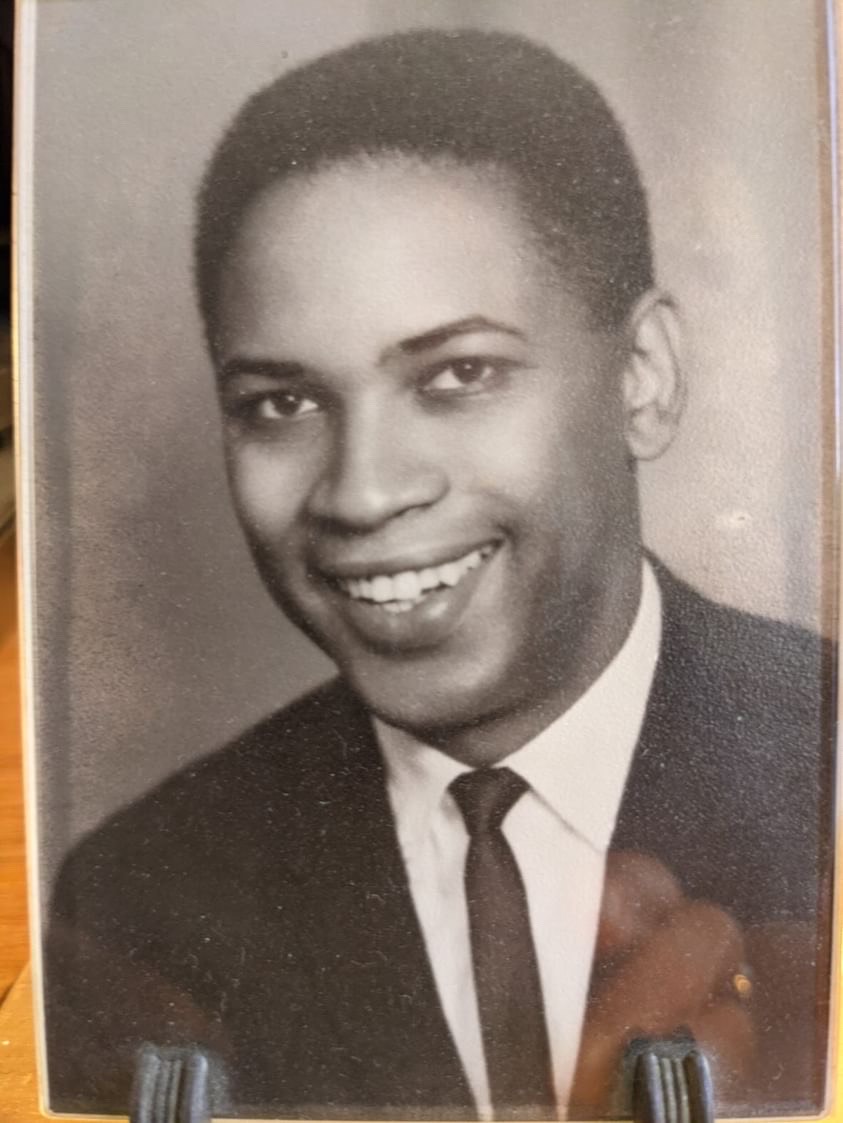

Samantha Bolton, second-year BA and the founder and president of OSA, opened the talk. She recounted a personal anecdote about her own family’s history with Tech, specifically that of her grandfather, Robert Cheeseboro, and his story with the Institute in the 1950s.

“I’ll make it very clear this event is not about my grandfather. This event is about Georgia Tech’s history. It’s about a history that doesn’t welcome acknowledgement, it’s not appealing, it doesn’t look good on the Georgia Tech website. This is about the full history, the whole history, not just the history that we want to see,” Bolton said.

Cheeseboro applied to Georgia Tech in 1953 as a transfer student from Morehouse College. At this time, Tech was still an all-white school and being a Black man, Cheesboro was denied admission based on his race. While she had heard parts of this story growing up, Bolton and her mother had to scour the internet and research files deep in the Library of Congress before they could find any tangible proof of this interaction.

“In this box was everything. It was the correspondence of a kid, once again at my age, asking, begging this institution to see him as human, to see him as an equal and then it contained the correspondence of the school saying you are not. For me, that was very hard to see,” Bolton said on the revelation of her family’s history.

Determined to share not only her own grandfather’s story but those of the many Black students before and after him, Bolton, as a writer herself, reached out to local news outlets to cover this story. Before she did, she contacted Tech’s administration for their input or any acknowledgement of this time in the Institute’s history.

“I called Georgia Tech. The person I spoke with will remain nameless … but I remember it sounded something like ‘This story looks bad on us. I don’t know what you want us to do about it.’ And so I spoke on the story,” Bolton said on why she chose share this story with the Technique.

Bolton’s drive to shed light on the past of this Institute extends beyond just her grandfather’s experience. With one Black student’s legacy unearthed from the depths of a dying archive, hundreds and even thousands more still remain in the dark.

“Collectively we are ignoring this history. We’re ignoring the fact that two generations ago our ancestors, our heritage, our grandparents couldn’t attend this institution … I’ve been begging the school to at least share the story. Not just the story, but the idea that this happened not just to him but to other people. Think about all the people that just didn’t dare apply for the safety of their lives, for every reason possible and so I beg the school to just at least acknowledge that any of this happened,” Bolton said.

Bolton asked Tech to recognize the broader narrative of its history of exclusion. Tech, like many other southern universities, has a past of institutional racism. Bolton emphasizes that although it is not something that can be reversed, Tech still has an obligation to address that part of itself. Ignoring or hiding the past only serves to suppress the ability to move forward into the future.

“A week ago I was in Student Ambassadors Diversity Equity Inclusion training … and during this training they’re telling us about the history that we should also address, we should talk about The Pioneers, we should talk about Robert Yancey, because that is Georgia Tech history. And I was sitting in this room holding back tears because I was thinking to myself, ‘My grandfather should be Georgia Tech history.’ He is Georgia Tech history. Everyone who didn’t get into Georgia Tech is Georgia Tech history, everyone that they kept out is Georgia Tech’s active history. And the repercussions of everyone that they kept out of this institution is Georgia Tech’s responsibility,” Bolton said.

The second part of the discussion was hosted by the GT Library, whose archivists had done research following a talk with Bolton, who wanted to find out more information on similar stories during the Institute’s period of race-based exclusion. Alex McGee, the University Archivist for Tech, opened with a lesser-known aspect of the famous Three Pioneers.

“Georgia Tech was the first public university in New South to integrate peacefully without a court order. That sounds really nice and it is factually true, but it belies the lived experience of the three men pictured here. The reality is that in 1961, Ford C. Greene, Ralph A. Long Jr. and Lawrence Williams became the first Black students to enroll at Georgia Tech. These students experience social isolation, discrimination, they were guarded by plainclothes policemen on campus, they did not get to live in the dorms, and the most telling fact is that none of these men stayed at Tech and graduated,” McGee said.

The Three Pioneers are often highlighted by Tech in a way that boasts the Institute’s own history and tolerance. But the reality of those three Black students’ experience and treatment at Tech are much different than what is commonly known.

Part of archivists’ work lies in uncovering these hidden histories. Alex Brinson, an Association of College and Research Libraries (ACRL) diversity resident, focuses on reparative description, which includes adding detail and context to pre-existing collections that prevent accessibility to those doing research.

“We had these records on Robert Cheeseboro and others in our tens of thousands of boxes and we just didn’t know, and, unfortunately, this is not uncommon. A lot of marginalized people’s stories get lost in history this way, they’re mislabeled or poorly described. And this isn’t just something that happens at Georgia Tech, it happens across the country in a lot of archives so it really is a testament to why this work matters,” Brinson said.

McGee explained the challenges of archival work heavily affects the oversight of marginalized people and communities.

Whether this is done intentionally or by accident, the work that archivists do to re-contextualize history is essential in preserving legacies and redefining our idea of the past.

“We will always be learning about Georgia Tech’s history and we will always be expanding our understanding of Georgia Tech’s history. We at Georgia Tech need to recognize that [it] is going to be iterative work, meaning we will always be building and redefining what it is we know about Georgia Tech,” McGee said.

Adaiba Nwasike, fourth-year PUBP, and Camille Trotman, fourth-year LMC, led the rest of the forum, culminating in an open Q&A session with Bolton.

The Georgia Tech motto of “Progress and Service” is often touted in the context of technological innovation of its students in corporate or research spaces. There is another aspect to this, however, involving Tech’s own narrative of its past and internal progression and disservice to marginalized communities.

Beyond the highlights advertised on its website or during tours, a more complete story of Tech’s history comes into view. This hidden history is what U.R.G.E. fights to remember and for the school to acknowledge. Find out more about GT NAACP on their Instagram, @gt_naacp.