Paper is everywhere. It is used daily for books, notes and receipts. People write on paper, crumble it up and discard it.

Few stop to consider all that goes into the construction of the very paper in their hand or all the potential that a single piece of paper has; however, on the afternoon of Thursday, Feb. 9, a group of artists, museum curators and Tech faculty gathered to celebrate the artistic function of paper.

Since Jan. 16, the Robert C. Williams Museum of Papermaking has hosted “Sustainability in Chaos,” an exhibit that encourages artists to use the medium of paper and environmentally conscious materials to show perseverance in chaotic modern times.

On Feb. 9, the museum hosted a reception where artists and curators could talk to the public about the works on display.

The museum is hosting this exhibit in collaboration with the North American Hand Papermakers (NAHP), an organization that connects papermakers from all across the United States.

NAHP invited members to apply to the exhibit, and two jurors, Helen Hiebert and Eileen Wallace, made the selections for the exhibit. The jurors chose 29 artists for the exhibit based on how the works matched the themes of surviving through a chaotic world and being environmentally conscious throughout it all.

Even though each artist made their work out of some form of paper, the artifacts that the exhibit showcased included elaborate sculptures and even a chair.

One sculpture, “Regulator” by John Vinklarek, is the artist’s interpretation of a ruined war machine. Another artifact, “Continua: Long Red Specimen,” by Milcah Bassel, is a long red folded origami-like paper that the owner could use as a wearable.

The Technique spoke to Jerushia Graham, a coordinator at the museum, about the art of papermaking and the exhibit that took place before the reception.

Graham said the museum first opened at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), formed from one papermaker’s collection. That papermaker was Dard Hunter, a man wholly fascinated with the process of papermaking and to whom Graham gave much credit for the museum.

“Dard Hunter is the whole reason that [the] paper museum exists. He was obsessed with hand papermaking and came from a newspaper family but was not very interested in school. As soon as he could, he decided he would not pursue a university degree and started traveling with his brother, who was a

magician,” Graham said.

On his travels, Hunter got involved with Roycroft, a reformist community of craft workers in the United States.

Roycroft found the skills Hunter learned while working at the family newspaper useful, and he helped the organization with much of its work, according to Graham.

Eventually, Roycroft decided to send Hunter to Europe to gain more training in stained glass, but while he was there, he saw an exhibit of papermaking and instantly became obsessed.

“From that point, he came back to the US, and he was determined to find papermakers in America, but he realized that because of the Industrial Revolution, nobody was making hand paper; they were all switching to machinery. Then, he decided he would learn how to do the craft by hand,” Graham said.

The rest is history. Hunter continued to travel and collect paper-making tools from all around the world to add to his collection and record papermaking techniques from all around the world. Graham said that by the time of his passing, Hunter had become the preeminent scholar on papermaking around the world.

Today, the papermaking museum has many tools and machines that Hunter collected over the years and rooms to hold papermaking workshops alongside space for a rotating exhibit, which Graham said the museum tries to coordinate with the change of semesters.

Graham explained that the Sustainability in Chaos exhibit was about confronting the world and society’s chaotic nature by helping people cope through art.

“The world has had a few rough years with COVID-19. We’ve also got conflicts of war and environmental problems. One of the things that art is great for is to be able to process and help make sense of our world. Sustainability and Chaos — how do we keep growing, thriving and living even in this chaotic world?” Graham said.

Graham showed the Technique some of the works in the exhibit and explained the emotional messages they can communicate about the human experience.

The first piece she showed, “Free Form” by Marjorie Fedyszyn, was six woven and tied abaca strips that appeared to tie together a bundle, but the items in the middle were missing. Graham said that this piece is one of her favorites at the exhibit.

“Here’s so much energy in life, but you get the feeling of someone’s hand having something captured at some moment. The way that [the abaca strips] fall, it’s not a machine. You can see it’s very organic,” Graham said.

Graham explained that she later learned the story behind this particular piece and had an even greater appreciation of the artistry and emotion of the work.

“I talked to the artist, and she said that she had a friend who committed suicide during the COVID-19 shutdown. She had some clothes that belonged to that friend, and she wrapped abaca strips around the clothing. Once those strips dried, they held their form, and she removed the clothing from before. It seems like such a beautiful way to remember someone. You see the evidence of them being here without the actual [material object],” Graham said.

Graham also highlighted a work called “Ghost of My Previous Bodies” by Neil Daigle Orians. The work is an expression of Orians’ struggle with his weight.

“Orians was hanging on to some clothes because he wanted to fit in them again and others to show how far he had come and say he was not going back to that. He was carrying clothes that weren’t functional in the ways clothes should be functional from place to place he moved in with him. And so he decided to repurpose some of the clothes,” Graham said.

Orians processed his old clothing into paper. Graham said that Orians also saved the stitching of the clothing — which can not be processed into paper — to contribute to sustainability practices and reincorporated it into the artwork.

The museum displayed all 29 artists and their artworks on Feb. 9 during a reception for the exhibit, which some artists, curators and campus faculty attended. The artists and papermakers discussed their work over refreshments in the lobby of the Paper Tricentennial Building, where the museum is located.

The Technique spoke to some of the artists about what inspired their work and what drew them to the papermaking field.

Kristen Tordella-Williams made a piece called “Scar VI” for the exhibit. She was inspired to create this piece during her time at the Tides Institute on an island in Eastport, Maine.

“On the island, there are remnants of the sardine industry everywhere. … With this work, I wanted to show the impact of the sardine industry on our bodies and planet,” Tordella-Williams said.

“Scar VI” uses a form of rust paint on silver-colored paper that resembles a piece of scrap metal that washed up on a beach.

Tordella-Williams said she started papermaking as an undergraduate student at the University of Massachusetts Dartmouth because she did not have enough money to buy paper for her artwork. She currently teaches art and art history at Auburn University in Alabama.

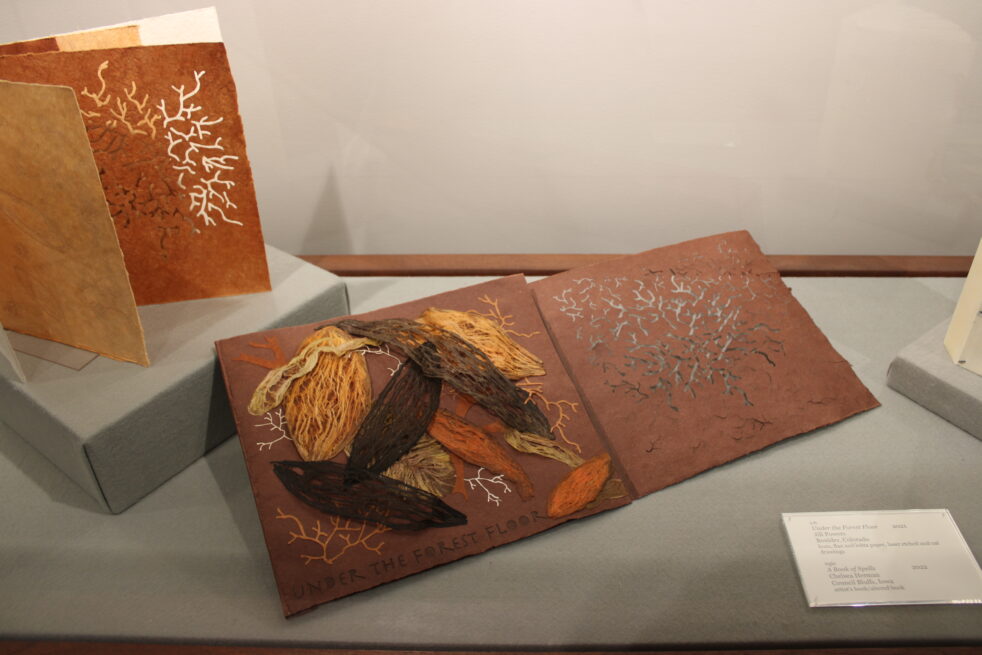

Jill Powers is another artist chosen for the exhibit. Her work incorporates fungi, mushrooms and mycelium into the art of papermaking by making paper and a book out of these plant materials. Powers explained that her papermaking career started when she took a class on painting different materials as part of her education as an artist.

“In a course I took on materials, we had the opportunity to make paper from plant material, and I have been doing it ever since,” Powers said.

As a member of NAHP, Powers explained that the organization is an excellent community of sharing, craftsmanship and artistry. Powers has been featured in collections nationwide and holds in person workshops for those interested in making paper from plant materials.

Jamie Bourgeois, an Atlanta area artist and gallery director of the Spalding Nix Fine Art in Atlanta, attended the paper exhibit even though she did not submit any work. Bourgeois explained that while she enjoyed all of the art present, she personally found the works that focused on sustainability most impactful.

“There is something about the full circle nature of a work that will eventually completely break down and return to Earth’s natural environment. It speaks to [the] ephemeral, fleeting feeling that everyone can relate to,” Bourgeois said, referencing “Artifact” by Anne Marble, a work made of paper pulp, wire and twine that will eventually deteriorate.

Bourgeois also said it was wonderful that Tech has a museum that can rotate exhibits like “Sustainability in Chaos” and that she would be returning to future events at the museum.

Virginia Howell, the museum’s director, also attended the event. She emphasized the importance that people come out and see what is happening at the museum. According to Howell, the museum struggles to attract visitors because it is on the edge of campus and currently lacks a meaningful way to engage with students and faculty directly.

“We are the only museum on campus, and we want to give back to our students. Our long-term goals are to support what students need academically, socially and emotionally. We want to provide a thought-provoking place where students can come and feel better,” Howell said.

A paper museum may not seem like the most exciting or stimulating place to many, but to the reception attendees, paper is everything. Speaking to the people at the event helps one realize that paper is so much more than a place to jot down notes.

Something about paper fills people up and releases an artist’s creativity. Many do not think about how paper is created even though they use and touch it daily. Even fewer know a simple piece of paper’s possibilities — what it can make and do. This small group, however, has unlocked the hidden secret of paper; they know its potential.

Graham’s mother, who watched Graham fall in love with papermaking throughout her life, also attended the reception. She put it best when she told the Technique that those who love paper love it because “they make it themselves. They can make anything out of their own two hands.” Those looking for more information on the museum can visit paper.gatech.edu.