Any institution that has lasted as long as Tech has been through enormous change and seen some monumental occurrences on its campus. The pathways and walkways around Tech are the same that Jimmy Carter and many other prominent figures used, but due to the constantly evolving nature of the campus, many landmarks have been altered or moved over time.

What was there 20 years ago may no longer be now. The change in scenery can impact more than just the landscape of campus. This article shares the story of one plot of land that represents change — not just on campus or in Atlanta but on a national level. In the 1940s and 1950s, Lester Maddox was an Atlanta area restaurateur who owned and operated a restaurant called the Pickrick at 891 Hemphill Avenue. Todd Michney, Associate Professor for the Institute’s School of History and Sociology, told the Technique about the restaurant’s history.

“The Pickrick was very popular with the surrounding working-class neighborhood and Tech students because of the low prices,” Michney said.

During the time, Atlanta enforced Jim Crow segregationist laws that had been in place since the first decade of the 20th century, and Maddox was a staunch supporter of segregation. The Pickrick was happy to serve its customers as long as they were white.

After years of civil rights challenges to Jim Crow laws in the South, Congress changed the status quo by passing the Civil Rights Act of 1964. The day after the federal law went into place, three Black men, George Willis Jr., Woodrow Lewis and Albert Dunn, attempted to enter the Pickrick to receive service, according to Michney.

“[The students] came here to try to gain access to the restaurant, and Lester Maddox chased them with a pistol, and his son brandished an axe handle. On one occasion, Maddox banged on the roof of one of the Black activist’s cars,” Michney said.

Michney emphasized that the three Black men were students at the International Theological Center in Atlanta, who felt it reasonable for them to have a cheap lunch at the Pickrick restaurant. Although they did not use violence, they were there to confront Maddox about his refusal to serve Black women and men, and Maddox responded by using weapons to force the men off of his property.

Janet Murray, Distinguished Professor for the Institute’s School of Literature, Media and Communication (LMC), leads a long-standing project to convey the event and its significance into an augmented reality experience. Murray told the Technique about the importance of this event and the involvement of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP).

“This is all choreographed by Constance Baker Motley of the NAACP Legal Defense Fund —the hero of civil rights legislation of the 1950s and 1960s. … She’s running the NAACP Legal Defense Fund, and she’s working with the ministers … to bring suit against the Pickrick the day after [the Civil Rights Act] was passed to enforce the law,” Murray said.

Motley successfully argued the case and had court orders handed out for the restaurant to desegregate, but Maddox refused. There were several more altercations between the men, and Maddox used several tactics to evade enforcement of the court ruling. At one point, he changed the name of the restaurant in an attempt to prevent enforcement, according to Murray. Finally, instead of integrating, Maddox sold the Pickrick to his employees, and the restaurant ceased operations. Tech agreed to buy the property after the restaurant shut down, which ended the public relations nightmare outside their campus, Michney told the Technique.

After Tech acquired the restaurant, they converted the building into a placement center known as the Ajax Building and later a police storage building. Tech used the building for nearly 40 years before demolishing it in 2008, according to Tech Communications. The Institute razed the building to make way for an expansion to the EcoCommons, which opened in 2021.

Murray and Michney told the Technique that there was very little signage detailing the site’s history for a while, but they hope their work will make the history more accessible to the general public. Murray’s augmented reality project allows users to interact with the site and see the events unfold as if they were there.

“It is very exciting to be on the site where history happened, then being able to see the past emerge. It’s as if you were experiencing time travel,” Murray said.

Murray said part of transporting the user back into history is making the viewer feel the impact of what was happening that day. She and her team are experimenting with ways to give the user a sense of how it felt to confront Maddox.

“We found that being in the car is a very powerful experience for people. There’s this moment where Maddox and his son are physically assaulting the vehicle and are menacing people within the car, and if we put the visitor in the backseat of the car with the three ministers who were trying to gain access to the restaurant, it’s a very visceral experience,” Murray said.

In the future, Murray hopes to release the augmented reality experience as a tablet application for anyone to download

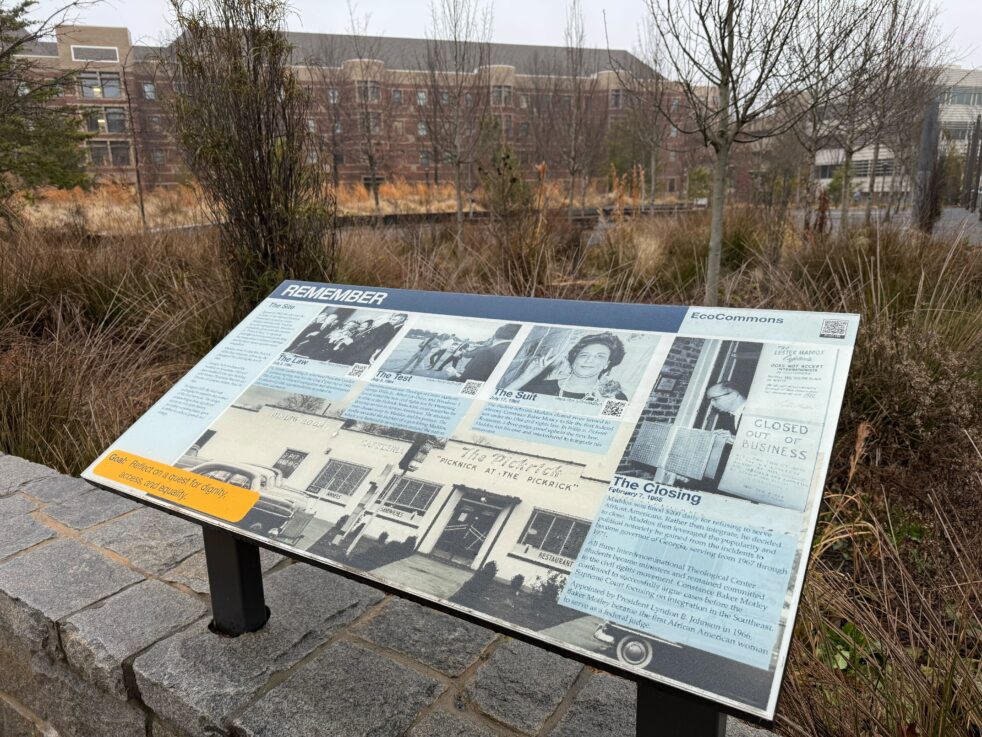

and use at the site. Authorities have erected memorials and signage recently to educate visitors about the events there. The signs tell the story of the site, starting from the opening of the Pickrick and culminating at the court decision that reaffirmed the Civil Rights Act and Tech’s purchase of the restaurant.

Jason Gregory, the Institute’s Landscape Architect, spoke about the design of the memorials and signage and how his department worked to preserve the site’s history while expanding the EcoCommons.

“When we were designing the space, and we realized the significance of this specific location from a cultural standpoint … it became an opportunity to create something a little more contemplative,” Gregory said.

The memorial consists of a low wall with three gaps. A tall stone slab stands away from each gap as if the slabs had been pushed a couple of feet out of the wall to their new resting spot.

“The wall represents the barrier the three individuals had to get past, and these three vertical concrete plinths represent them pushing the barrier away. There are also three large seating benches, as well as three longleaf pines, which are all representative of the three individuals that were willing to stand up to Maddox,” Gregory said.

Gregory further explained that the three pine trees are the only pine trees in this area of the EcoCommons, and as they grow, they will become very prominent in the landscape. The memorial also includes a steel barrier that outlines where the restaurant once sat. In his role as the Institute’s Landscape Architect, Gregory said that he sees a design trend that looks back at historical events and ensures that we are remembered in the modern landscape

and architecture.

“It is eye-opening to see that not just this place but other places like this are becoming more important and that people are remembering and trying to call attention to these landscapes or locations that may be completely different than they once were,” Gregory said.

It took years for the memorials and recognition to be implemented as institutional priorities and funding changed. Now, Michney sees the site as a representation of repair and sustainability by combining the EcoCommons with the story and message of what happened at this plot of land 60 years ago.

“I think this memorial has the potential to revisit history thoughtfully; in the larger context of ecological sustainability and ecological repair, we could also think of repairing relations between Black and white people in this country,” Michney said.