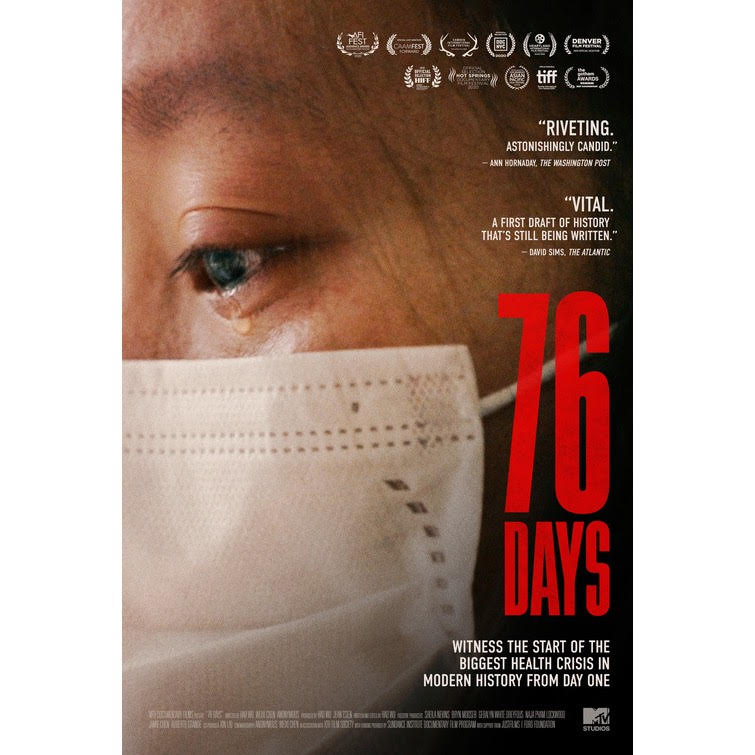

On Thursday, Feb. 4, a panel of Tech professors discussed the critically-acclaimed documentary “76 Days,” a film about the COVID-19 outbreak in Wuhan, with its lead director, Wu Hao.

The event was the first in the ongoing annual Global Media Festival, the theme of which this year is sustainable cities and communities.

The documentary opens on a note of heartbreak. A nurse in Wuhan is held back by her colleagues as her father takes his last breaths.

At the beginning, the film conveys the utter confusion that defined the beginning of the pandemic for medical staff worldwide.

Angry patients clamber to enter the hospital, while exhausted doctors struggle to hold them back. By the end, many patients are happily recovered, but an overwhelming number have died. The sound of sirens in Wuhan to mark the city’s mourning of the dead is the chilling end to the movie.

Hao explained the initial inspiration for the film.

“I usually don’t cover topics already covered widely by the media, but COVID was personal,” Hao said.

Hao flew home to spend Chinese New Year of 2020 with his family in Shanghai.

“There was only a rumor of a few odd pneumonia cases coming out of Wuhan. Shanghai is China’s largest city, so there are usually people on the streets celebrating, but last year no one was out,” Hao said. “This left a lasting impression on me. It felt like a sci-fi movie.”

A U.S. network approached Hao about making a movie about the outbreak.

“Although they pulled out later, I continued,” Hao said. “The first footage I got expressed the rawness and the nakedness of the hospital so well.”

Dr. Jin Liu, professor in the School of Modern Languages, asked about the ethics of shooting disease and death.

Hao explained that typically, he would do research and plan the documentary, but that in this case, his co-directors started shooting before he even approached them.

“Sometimes they’d follow a character and then this character would deteriorate or die — like a warzone. I told them just to capture everything, to treat it like a war. I like that [my co-directors] show empathy,” Hao said.

By April, when Hao began editing the film, he had seen some footage of hospitals in New York and Italy, but didn’t feel that enough raw realism had been shown.

“I wanted to document for history the true horrors of this pandemic. We had a lot of podcasts out with people telling us how horrible the disease was, but no visual evidence,” Hao said. “I feel like the camera should not look away when tragedy happens. We tried to maintain the balance between respect and realness.”

Dr. Amanda Weiss of Modern Languages pointed out the natural, realistic cinematography and the interpersonal moments of hope that filmmakers were able to capture. When Weiss asked how Hao found these moments to highlight during editing, he answered that he sensed his collaborators were very sensitive to emotions and details.

“In the beginning it’s about chaos, fear, the unknown and gradually you see things start to get under control,” Hao said. “As soon as this happens, life comes back. As we see the city recover, we see humor return. We see the people become more hopeful.”

Hao pointed out the differences between this film about such a rapidly changing pandemic and other previous films.

“I’ve never had the most emotional point of the film happen at the beginning — usually you wait for the climax — but this is the way life works. But there’s not really a happy ending — the people come together to grieve,” Hao said.

Dr. Michael Elliott of the Schools of City and Regional Planning and Public Policy noted the historic role of cities in pandemics as gateways to infectious disease.

Elliott mentioned the dual nature of cities as places with the best healthcare but also the highest risk for spread. He asked about how Hao decided to present Wuhan.

“For a lot of us, our instinct was to document the city lockdown,” Hao said. “My team filmed more than what we show in the current film. There was no public transportation during the lockdown, so a lot of people relied on volunteer drivers.”

Hao’s team also filmed some scenes inside of homes, but ended up giving up on that idea.

“We didn’t have a permit to show places outside the hospital,” Hao said. “People would stop us from filming the city. Secondly, to make an emotionally resonating film, we wanted to focus on the raw humanity inside the hospital.”

Hao explained the censorship his team has faced since releasing the movie.

“Since March, China’s government has officially tried to control any narrative about the pandemic,” Hao said. “The censors would not approve the release of this film in China. I didn’t want to deal with the censors. My co-director remains anonymous because he exists in the system. Anyone now in China is very careful about saying anything.”

Technique asked whether Hao approached the film from a political perspective given the United States’ racist attitude toward the virus.

“When you edit, you don’t rationalize too much,” Hao said. “You follow your emotional instinct. Looking back, though, a lot was impacting me. When I was editing, the American response was completely losing control. There was a lot of anti-Asian sentiment. All of this was definitely subconsciously influencing me. Working on this film saved me a little, I think. It showed me a glimmer of hope.”

Hao emphasized the stark contrast between the horror and kindness of humanity that has emerged during the pandemic thus far.

“Pandemics always bring out the worst in human beings. We always find scapegoats. I want to show people that COVID is real… Let’s not just focus on the numbers, or the politics, but the humans, the individual stories that can easily get lost,” Hao said.

“My team filmed more than what we show in the current film. There was no public transportation during the lockdown, so a lot of people relied on volunteer drivers.”

Hao’s team also filmed some scenes inside of homes, but ended up giving up on that idea.

“We didn’t have a permit to show places outside the hospital,” Hao said. “People would stop us from filming the city. Secondly, to make an emotionally resonating film, we wanted to focus on the raw humanity inside the hospital.”

Hao explained the censorship his team has faced since releasing the movie.

“Since March, China’s government has officially tried to control any narrative about the pandemic,” Hao said. “The censors would not approve the release of this film in China. I didn’t want to deal with the censors. My co-director remains anonymous because he exists in the system. Anyone now in China is very careful about saying anything.”

Technique asked whether Hao approached the film from a political perspective given the United States’ racist attitude toward the virus.

“When you edit, you don’t rationalize too much,” Hao said. “You follow your emotional instinct. Looking back, though, a lot was impacting me. When I was editing, the American response was completely losing control. There was a lot of anti-Asian sentiment. All of this was definitely subconsciously influencing me. Working on this film saved me a little, I think. It showed me a glimmer of hope.”

Hao emphasized the stark contrast between the horror and kindness of humanity that has emerged during the pandemic thus far.

“Pandemics always bring out the worst in human beings. We always find scapegoats. I want to show people that COVID is real… Let’s not just focus on the numbers, or the politics, but the humans, the individual stories that can easily get lost,” Hao said.