The tagline of Bruce Robinson’s The Rum Diary boasts, “Absolutely nothing in moderation.” While this philosophy would naturally befit a film adaptation of the semi-autobiographical novella of the same title penned by gonzo journalist and professional nihilist Hunter S. Thompson, the film crew responsible for its production delivers a surprisingly low-key homage to Thompson’s years as a budding anti-authoritarian. The film leaves the viewer mildly amused with little thematic substance to chew on.

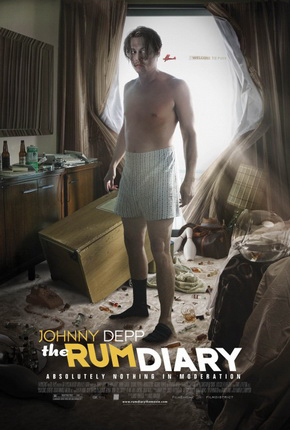

The picture opens on an ebullient, 1960s San Juan, Puerto Rico, where protagonist Paul Kemp (Johnny Depp) is slated to work for an English-language newspaper that is doomed to fold. As Kemp catches wind of the lavish scenery and political tumult of the U.S. territory, he also falls prey to the likes of the unctuous and influential Sanderson (Aaron Eckhart), who seeks a skilled writer to promote the sale of virgin Puerto Rican soil to American investors and developers. Thompson’s alter ego experiences a few unpleasant brushes with the law and locals, who are well weary of inebriated Americans driven to excess, and he also becomes painfully enamored of Sanderson’s fiancée, Chenault (Amber Heard).

Although the film’s heart is in the right place—Depp himself, a close friend of the late Thompson, pressed for its production with the intent of paying tribute to the novelist—the episodic format of the picture largely amounts to a series of dead ends. The film keeps the audience more or less entertained as it follows Kemp through seaside joy rides, Puerto Rican cockfights, clumsily rendered interplay with the willful Chenault, along with a gratuitous acid trip sequence, yet the period piece never quite captures the essence of the political upheaval—the fear and loathing—of the time and place that drove Thompson to serve as a journalistic voice for the weak and the socially damned.

The film’s resolution is also somewhat murky. As Kemp claims to have discovered “the connection between children scavenging for food and shiny brass plates on the front doors of banks,” and declares, “I will try to speak for my reader. That is my promise,” one gets the feeling that the filmmakers are as unsure of this self-realization as the audience. The closing scene keeps the viewer guessing as Thompson’s alter ego sails off into an uncertain sunset, never having revealed what exactly he has gained or lost from his stint as a journalist in San Juan.

Robinson’s production is lacking in thematic foundation, but the film demonstrates a few golden flashes of light in the proverbial pan. The stark contrast between shots of schoolchildren living in squalor and the extravagant lifestyle of American expatriates brings attention to the financially -polarized class system of an industrializing Puerto Rico—not to mention the former parasitic relationship between the United States and the economic output of its Caribbean territory.

Kemp and his oddly charming cohort of drunken, misfit journalists also serve to keep the film afloat. Sala’s (Michael Rispoli’s) grinning nihilism and the antics of Moberg (Giovanni Ribisi), an alcoholic reminiscent of the drunken mouse found in Disney’s Alice in Wonderland, deliver laughs and good humor in the form of slapstick comedy and booze-addled camaraderie in spite of the film’s darker undertones.

Depp and Robinson mean well, but The Rum Diary ultimately fails to realize Thompson’s unorthodox lifestyle and the political unrest of the early 1960s.

While the central thesis of the film remains unclear, these glimpses into the drunken diversions of Thompson’s younger years carry hints of the “restless idealism…and…sense of impending doom” that came to define his career.