Editor’s Note: The language used to describe many of the organizations and events contained in this article reflects the rhetoric of its time. It is not the intent of the author, editor or the Technique to be insensitive or offensive, but merely to accurately describe the history contained in this piece.

Across every major league baseball park in America, there is one retired number that always hangs in the rafters, honoring the legacy of one of the most famous athletes in American history.

42, worn by Jackie Robinson.

For decades, the MLB has broadcasted Robinson’s story in the name of racial equality. However, the league recently acknowledged its role in the ideological and physical destruction of the Negro League (NL) — the league that recruited and developed Robinson.

The first African American player on a professional baseball team was actually Bud Fowler in 1872. He was so talented that despite racial and social beliefs during his time, he played on all-white teams. However, he had to move around the country to play in different organized leagues due to racial tensions and poor team finances.

Enter Rube Foster, a Black pitcher who traveled across the country to play in spite of rules barring him from the professional level. He negotiated a deal for the Chicago American Giants to play at South Side Park as the first professional Black baseball team. The Giants were joined by new teams seven years later as Foster and his fellow owners organized the Negro National League (NNL) in 1920. By 1921, they were drawing crowds of 200,000 spectators.

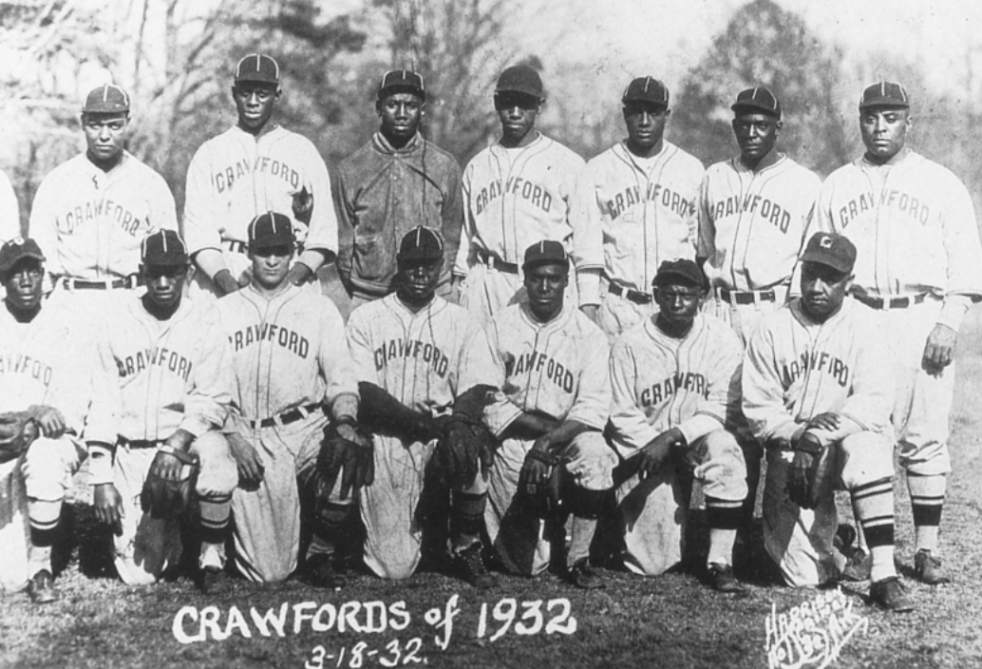

Even though the NNL could not survive the Great Depression, the league was revitalized in 1933 as the Negro American League (NAL) with a new concept: the East-West All-Star Game. Throughout the thirties and forties, spectators showed up in hordes to watch some of the best baseball players in the nation.

Robinson was far from the only star — he was not even the consensus best player. Pitcher Satchel Paige’s dominance on the mound and catcher Josh Gibson’s powerful bat rivaled Robinson’s speed as a baserunner and shortstop. Center fielder “Cool Papa” Bell, center fielder Oscar Charleston, outfielder Monte Irvin, pitcher Martín Dihigo, first baseman Buck Leonard — all of these players made it to the Baseball Hall of Fame in 1972.

Despite their inclusion in the Hall of Fame, the accomplishments of the players and teams in the NAL were not always recognized. In the late 1960s, the Special Baseball Records Committee excluded recognition of the Negro Leagues as major league caliber. Yet, in 1942, the crowds at NAL games numbered in the millions. In December 2020, MLB Commissioner Rob Manfred announced that the seven Negro Leagues would be receiving Major League Status — 100 years after the first Black baseball league was founded.

Baseball-Reference, the largest baseball statistics page, added data from the NL into their records in 2021. Fowler was only named to the Hall of Fame in 2022. Furthermore, FanGraphs, a modernized version of Baseball Reference with in-depth statistics, added data on Feb. 14 of this year. In a sport as statistics-driven as baseball, the omission of these numbers denied these players of another metric to display their greatness.

An example of this is Paige. In his youth, his fastball was a powerful rocket that could be launched from nearly any angle. He worked a hesitation into his delivery that drove batters crazy as they attempted to guess when he would release it.

In an act of competitive pettiness, he struck out a batter who claimed Paige had no curveball, using only curveballs. At the age of 42, he finally made his MLB debut. He pitched three complete MLB games without a relief pitcher, garnered a 2.48 earned-run-average (ERA) and won a World Series. In short, his technique and approach to pitching belonged in a different era.

Yet, up until 2021, he only had a career win above replacement (WAR) of 7.3. With the new data, his career WAR is estimated at 47.6 on Baseball Reference and 43.6 on FanGraphs. This ranks him in the top 100 pitchers ever.

The appearance of Paige and Robinson in the MLB marked the end of the NL. Two of the NL’s most marketable stars left the league for the opportunities and recognition afforded by the MLB’s bigger budget, larger audience and greater recognizability. NL owners began to sell their teams in 1948 and the league officially folded in 1960, seeing their crowds dwindle and their players decline in quality as more and more left for “the majors.” Yet, if the NL had been able to develop within the MLB, the talent of Black baseball players would have been officially and culturally recognized from the very beginnings of professional baseball.

Ultimately, it is good that this longstanding and purposeful oversight is being corrected. However, it is important to remember the calculated effort made to remove these players’ statistics from baseball discourse. The MLB made the decision to keep the NL separate, poached their best players once they saw their talent, watched the wild popularity of the league fade and took decades to honor the statistical performances of some of the best baseball players ever purely because they came from the NL.

Today, the MLB makes retro jerseys of NL teams and fans can play with those teams in the MLB’s official video game, MLB: The Show. They attempt to portray the league as integral to baseball history when they worked so hard to separate it from that same history.

It is up to baseball fans to remember the talent and perseverance of members of the seven Negro Leagues, and it is up to the leagues today to honor their legacy and contributions to the sport.