The High Museum of Art recently unveiled its newest temporary exhibit featuring the works of pop art icon Andy Warhol. The exhibit, which contains over 250 of Warhol’s works, traces the artist’s incredible career from his beginnings as a marketing illustrator in the late 1940s through his rise to become one of America’s most famous and controversial artists.

The collection contains mostly silkscreen prints, a type of photograph reproduction that belongs traditionally to the advertising world and that Warhol pioneered as a serious art form. Warhol used this process to create his most famous works of art, and it gave his works their striking, vibrant — at times even harsh — character.

Visitors to the exhibit can find the full range of Warhol’s works, from prints of Civil Rights era photos to images of Mick Jagger to Warhol’s ubiquitous Campbell’s soup cans. Some of the most interesting items in the collection are Warhol’s darker and lesser known pieces.

A macabre 1971 series of prints of an empty electric chair features intense distortion and discoloration, producing a chilling, disturbing effect for the viewer and making the prints difficult even to look at.

Equally disturbing is a 1964 reproduction titled “Birmingham Race Riot” which depicts police brutally beating African Americans at a peaceful protest march. These pieces remind the visitor that the period in which Warhol worked was not all about bright colors and big parties — it was also one of the most turbulent eras in American history.

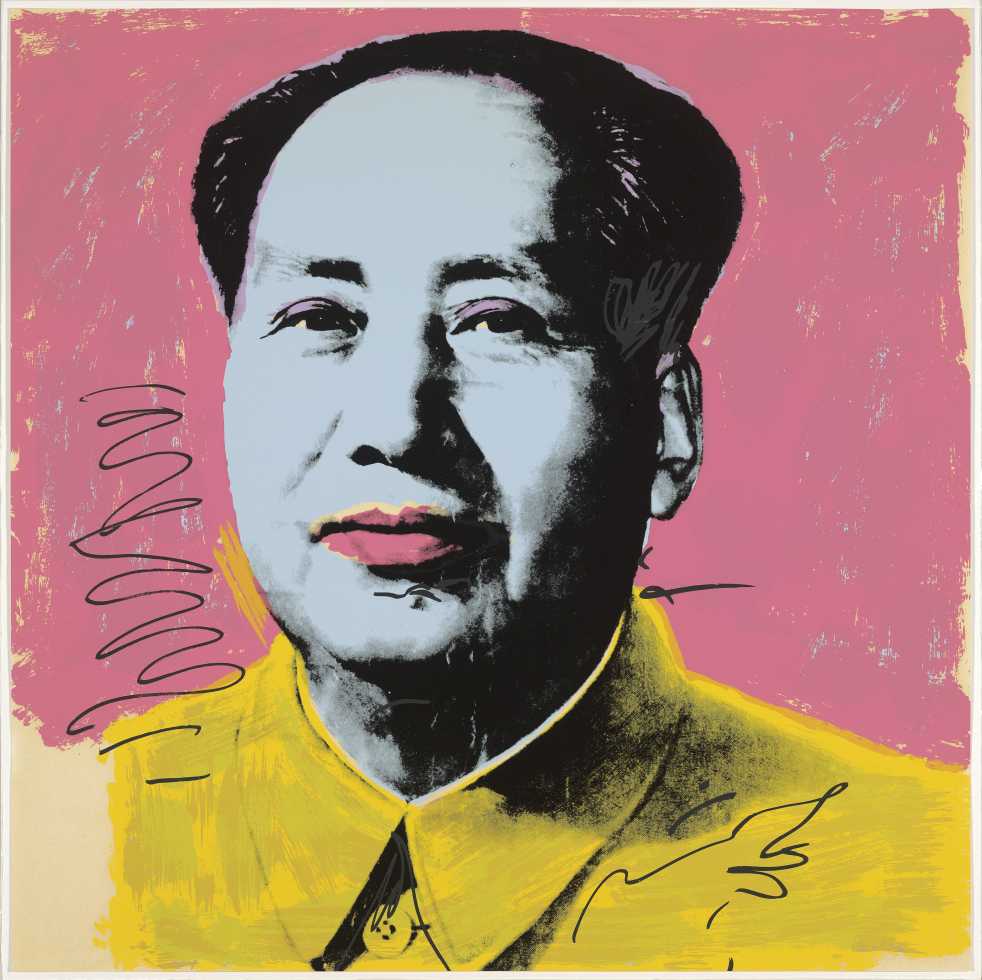

Still, the majority of the exhibit is filled with the bright, poppy images that are more well known and closely associated with the artist: the iconic 1967 print “Marilyn Monroe,” 1975’s “Mick Jagger” and, of course, plenty of Campbell’s soup cans. Among the most memorable works in the collection is a series of prints produced in 1972 titled “Mao.” The prints are reproductions of a portrait of communist Chinese leader Mao Zedong that recolor and distort the tyrant’s face, making him appear grotesquely phantom-like and ill.

The exhibit is housed in a relatively small space, making the experience of walking through it overwhelming and at times disorienting. At first it seems odd that the museum’s curators would do this to their guests. There are plenty of massive exhibition spaces at the High where the 250 works in this collection could be housed comfortably.

The sense of disorientation produced by the exhibit’s densely packed walls, however, is the whole point of going to a Warhol exhibit. A person walking through the gallery would have trouble focusing on any given work for very long. It is not that the works are not eye-catching and engaging; rather, each work is so flashy and exciting that it is nearly impossible to look at one without being distracted by all the others.

Warhol made his prints this way because he wanted the observer to feel distracted, lost and disoriented. He confronts Americans with what should be familiar icons of their culture — Campbell’s soup cans, Marilyn Monroe and Mick Jagger — and twists, distorts and discolors them in a way that makes them feel like travelers in a foreign land.

In disorienting his consumers, Warhol makes many different points about commercialism and American culture, which are open to interpretation, but undoubtedly he wants them to feel lost. The curators of the exhibit are certainly aware of this and did an excellent job of creating an exhibit that Warhol would be proud to visit.

The exhibit runs through Sept. 3, and visitors can attend for free on the second Sunday of each month. For those willing to pay for admission, the museum offers an enticing bonus on the third Friday of every month: a live four-hour jazz performance in the main atrium. After all, there exists no better complement to an exhibit on one of America’s greatest native artists than America’s greatest native musical form.